Teacher Education Quarterly

The Rise of the Life Narrative

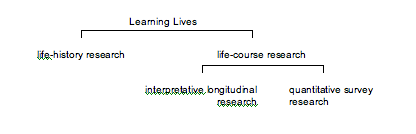

What makes the project relatively unique is not only its length (a data-collection period of almost three years) and size (about 750 in-depth interviews with 150 adults aged 25 and older, plus a longitudinal questionnaire study with 1,200 participants), but also the fact that it combines two distinct research approaches, life history research and life-course research, and that within the latter approach, it utilises a combination of interpretative longitudinal research and quantitative survey research.

In the Learning Lives project we have the chance to see how life history can elucidate learning responses. What we do in the project is to deal with learning as one of the strategies people employ as the response to events in their lives. The great virtue of this situation regarding our understanding of learning within the whole life context is that we get some sense of the issue of engagement in learning as it relates to people living their lives. When we see learning as a response to actual events, then the issue of engagement can be taken for granted. So much of the literature on learning fails to address this crucial question of engagement, and as a result learning is seen as some formal task that is unrelated to the needs and interests of the learner. Hence so much of curriculum planning is based on prescriptive definitions of what is to be learnt without any understanding of the situation within the learners’ lives. As a result a vast amount of curriculum planning is abortive because the learner simply does not engage. To see learning as located within a life history is to understand that learning is contextually situated and that it also has a history, in terms of (a) the individual’s life story, (b) the history and trajectories of the institutions that offer formal learning opportunities, and (c) the histories of the communities and locations in which informal learning takes place. In terms of transitional spaces we can see learning as a response to incidental transitions, such as: events related to illness, unemployment and domestic dysfunction, as well as the more structured transitions related to credentialing or retirement. Hence, these transitional events create encounters with formal, informal and primal learning opportunities.

How then do we organize our work to make sure that our collection of life narratives and learning narratives does not fall into the traps of individualization, scripting, and de-contextualization? The answer is we try to build in an ongoing concern with time and historical period, and context and historical location. In studying learning, like any social practice, we need to build in an understanding of the context, historical and social, in which that learning takes place. This means that our initial collection of life stories as narrated moves on into a collaboration with our life storytellers about the historical and social context of their life. By the end we hope the life story becomes the life history because it is located in historical time and context.